What can't a regular expression do?

Structure of regular expression

A language is a set of strings accepted by a computing system-in this case, by a regular expression. We try to model computing as decision problem of checking whether a particular element belongs to a set or not. The expressibility of regular expression is nothing but what sets can and cannot be defined through regular expressions. We need to define our structure of regular expression properly to infer some of the properties that it could carry. We define regular expression inductively as follows

One of the first properties of regular languages is that any finite set of strings is regular. This is because we can simply join the strings using the + (concatenate) and | (union) operators in a regular expression to build regular expression for any finite set. Therefore, the real challenge lies in understanding which infinite sets can or cannot be described by regular expressions.

Ultimately periodic

If we take a infinite regular set and sort it by the length of the string, the length would eventually be periodic. What ultimately periodic means is that, the length of a string will eventually be regularly spaced by a constant or a finite set of constants from other, For example,

There need not a be a single constant, consider the regular expression $a(bb\shortmid ccc)\ast d$ there are 2 constants here and every string should have length either 2 or 3 more than another if you start taking considerably long strings. With finite sets this aint true, thats exactly why its "ultimately" periodic.

Any set of string which doesn't have this property is said to be not regular and hence can't be recognized or matched by a regular expression. For example, $b^k$ ie., $b$ repeated $k$ times where $k$ has to be a perfect square, is not a regular language. Since its infinite and not ultimately periodic. This method is not very useful to distinguish all non-regular languages to be not regular. Since length of context free language (properly formed html is one) is also ultimately periodic.

Pumping lemma

This is the fool proof way to say whether a particular language is regular or not. Formally, pumping lemma states that if there is always a way to partition any string in a regular language of length more than some $p$ as $$xyz$$ such that $$xy^nz$$ also belongs to the language, where $len(y) \ge 1$ and $len(xy) \le p$ and $$n \ge 0$$.

Some examples.

- Set of all strings on $$\{a\}$$ with length multiples of $$4$$ is definitely regular. Where $$p=4$$ $$x=\epsilon$$ $$z=\epsilon$$

- Set of all strings of form $$ab*a$$ is also regular (actually definition itself is a regular expression) where $$p=3$$ $$x=a$$ $$z=a$$

Some non examples

- Set of all strings of the form $a^nb^n$, has no division for any finite $p$. If $y$ is just $a$'s or just $b$'s then the pumped value will have more $$a$$'s than $$b$$'s and more $$b$$'s than $$a$$'s respectively. If it contained both $$a$$ and $$b$$ the pumped string wont have the form all $$a$$'s followed by all $$b$$'s

- Set of all well bracketed expression, ie., bracket matched perfectly $$\{(,)\}$$. If $$p \le 6$$ consider the string $$(())()$$ which has no partition, if $$p \le 8$$ $$((()))()$$ and so on so forth. We can give a counter example for every choice of $$p$$

The intuition is simple, only case where a regular language is not a finite set is when it has a *Kleene star* in its regular expression. Pumping is a way to clearly express what Kleene star does.

Myhill-Nerode

One other good way to find if a language is regular, is by finding prefixes of a language that could be distinguished. Distinguished here mean, if $u$ and $w$ are prefixes of strings in a regular language, they are indistinguishable if for all suffix $x$ either both $ux$ and $wx$ are part of the language or both aren't. We put such indistinguishable strings in a partition. If a language has finite number of such partitions then its regular otherwise it isn't

Some examples

- Set of all strings on $$\{a\}$$ with length multiples of $$4$$, have 4 partitions where any string of length $$l$$, $$l \% 4 = 1$$, $$l \% 4 = 2$$, $$l \% 4 = 3$$, $$l \% 4 = 0$$

- Set of all strings of form $$ab*a$$, have 3 partitions $$\epsilon$$, $$ab*$$, $$ab*a$$

Some non examples

- Set of all strings of the form $$a^nb^n$$, has infinite such partitions since for each $$k$$ $$ab^k$$ suffix is accepted only for prefix $$a^{k-1}$$.

- Set of well bracketed expressions, also has infinite such partitions, since for each $$k$$ $$)^k$$ suffix is accepted by only prefix(es) that needs $$k$$ closing braces to match.

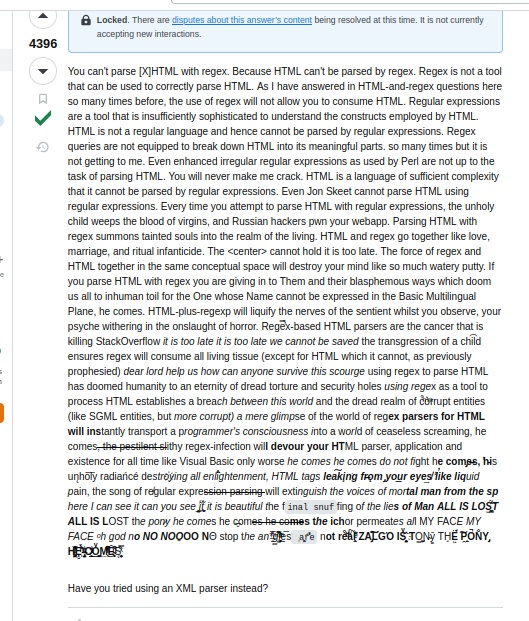

- Well formed html documents are a more general case of well bracketed expression. If we consider opening tag as open brace and closing tag as closing brace.

The intituition is, each such partition can be modelled as a state in the DFA, since any two prefixes become indistinguishable when it reaches the same state. This theorem is usually used to find minimal DFA, but can also be used to find whether a language is regular or not.